Uber and Lyft Sued for Patent Infringement

Takeaway: Hailo Technologies, LLC filed a complaint for patent infringement by Uber and Lyft for their software system that allegedly infringes Hailo’s software patent for an “automated vehicle dispatch and payment honoring system.”

Image from http://www.newsweek.com

Hailo Technologies LLC’s patent, filed in 1997, was directed to a software system that allowed a user to pick through a menu for a transportation means of his or her choice and enter the number of passengers and then show the estimated cost of the ride.

Hailo Technologies LLC’s patent, filed in 1997, was directed to a software system that allowed a user to pick through a menu for a transportation means of his or her choice and enter the number of passengers and then show the estimated cost of the ride.

Hailo Technologies LLC is not to be confused with Hailo, a well-known ride-hailing business based in Europe that merged with myTaxi last year. Hailo Technologies LLC was incorporated last year and is represented by Cotman IP Group, a firm known to represent patent trolls.

Uber recently launched a patent purchase program called UP3 in an attempt to increase its IP holdings to protect itself from suits like this one. It will be interesting to see if Uber is willing to fight back based on principle or if it will use its new patent purchase program to settle the case quickly.

KFC Sues Small Business for Trademark Use of “Finger Lakin’ Good”

Image from https://www.gofundme.com/fingerlakingood

Takeaway: Small business in New York is fighting back KFC for its use of “Finger Lakin’ Good” which KFC alleges is infringing on its famous slogan “Finger Lickin’ Good.”

A New York-based family-owned business for a 70-acre development intended to include a brew hub, a pavilion, and a sunflower patch wanted to use the slogan “Finger Lakin’ Good.” The owner, Brian Mastrosimone, developed the slogan based on a clever play on words given that his development is set alongside one of the many lakes in New York known as the Finger Lakes.

KFC Corporation sued Mastrosimone for alleged trademark infringement of its slogan “Finger Lickin’ Good,” which KFC claimed to be its oldest and most important trademarks from the 1960s. KFC claimed that Mastrosimone’s slogan is too similar that it draws a false connection and may confuse consumers and further preys on and potentially damages the goodwill developed by KFC over the years. KFC was further concerned that consumers would assume that Mastrosimone’s products and services were connected to or endorsed by KFC.

Mastrosimone argued that his business is not related to fast food and that his logo looks completely different from KFC’s such that there would not be any confusion. Mastrosimone was advised by trademark attorneys to change his tagline, despite the fact that his trademark application was approved by the Trademark Office, because of the hefty legal fees that he would incur to battle a large corporation like KFC.

Mastrosimone has started a GoFundMe campaign to hopefully help offset the legal fees as he tries to fight back. So far, it does not look like he has garnered sufficient financial support for the impending legal battle. We look forward to seeing how this case is resolved.

Trademark Battle over “Meowington”

Takeaway: Joel Zimmerman, also known as Deadmau5, must rely on common law trademark rights to protect the trademark for his beloved celebrity cat, Professor Meowingtons, because he failed to register the federal trademark back when he first used the mark in commerce in 2011. However, he will have a difficult time in obtaining the full federal rights to the mark since the mark was registered by Emma Bassari in 2014 for an online retail store for cat enthusiasts. Registering federal trademarks should be a priority for any business owner to avoid messy litigious situations such as this one.

In 2010, Joel Zimmerman, also known as Deadmau5, adopted his cat, Professor Meowingtons, who has garnered tens of thousands of followers across different social media platforms.

In 2014, Emma Bassiri created an online retail store for cat owners and cat enthusiasts called Meowington and has been one of the most successful boutique online shops in its niche market. Bassiri applied for the trademark “Meowington” in July of 2014, and without any opposition, was granted the trademark rights in 2015.

Zimmerman filed a petition with the United State Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) to cancel Bassiri’s trademark after he was made aware of Bassiri’s trademark because his application for Professor Meowington was rejected. Zimmerman claims that Bassiri was a longtime fan of his music and used the mark as an attempt to draw a false connection between her store and Zimmerman’s cat.

While Bassiri is seeking, inter alia, declaratory judgement as to ownership and priority of right, trademark infringement, and unfair competition, Zimmerman is hoping to rely on common law trademark rights that he claims started in 2011 in the new federal suit in the Southern District of Florida.

We will have to wait to see how the litigation proceeds and will report accordingly.

Snap Acquires Geofilter-Related Patent for $7.7 Million

Takeaway: Snap’s number one stream of revenue was based on selling geofilters and now it finally owns the patent related to the method and system of providing visual content editing functions.

Snap’s acquired patent was filed by Molbi, an ex-competitor of Instagram, in 2012 and is directed specifically to server-side filters so the app does not need to be updated every time there is a new geo-filter.

Mobli’s co-founder Moshe Hogeg sold the patent (US# 2016 0373805, US# 9,459,778) to Snap for $7.7 million, which is believed to be the highest amount paid for a patent from the Israeli tech industry. However, based on Snap’s S-1 filing for its IPO, of the $400 million in revenue, a whopping $360 million was based on selling geofilters, so it was well worth the price.

Owning the patent has secured Snap from lawsuits relating to its geofilters, or at least has given it leverage against its competitors such as Facebook, which has been known to copy many of the features of Snap and even surpassing Snap in user base, such as the feature Instagram Stories.

Beyoncé Sued For Copyright Infringement For Copying Phrases in Her Song “Formation”

Image from http://rhymejunkie.com

Image from http://rhymejunkie.com

Takeaway: The estate of Youtuber Messy Mya filed a suit against Beyoncé for copyright infringement for sampling Mya saying, “what happened in New Orleans?” in the beginning of “Formation” without permission. The voice sample is hard to dispute as any voice other than Mya’s so it will be interesting to see how Beyoncé’s counsel will try to refute such claims.

Anthony Barré, also known as Messy Mya, was a highly recognizable New Orleans artist, DJ and YouTube star. Mya’s estate is seeking “more than $20 million in back royalties and other damages” and also named Sony Music, Jay-Z, and other songwriters as named entities in the suit. This is not the first time that Beyoncé has been sued for sampling parts of other artists’ music or artistic works.

Mya’s estate stated that it “received nothing…no acknowledgment, no credit no remuneration of any kind” after attempting to reach out to Beyoncé for using Mya’s voice sample without their permission.

The lawsuit argues that “[t]here should be no doubt that Anthony Barré’s unique, gravelly voice, cadence and words were sampled by defendants.” When listening to Beyoncé’s “Formation,” it is fairly obvious to a layman’s ear that it is Mya’s voice that was sampled.

“Section 107 of the Copyright Act provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research—as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use.” Beyoncé could argue that the use of the sample was making a “political statement” and therefore would be fair use, however that most likely will be an uphill battle.

However, because “Formation” was a chart-topping, Grammy-nominated song, and worth millions, the political undertones may not be sufficient to persuade a judge to consider that fair use.

PTAB Is Not Bound to District Court’s Holding of Nonobviousness and Vice Versa

Takeaway: The PTAB and district courts are not bound by each other’s contrary decisions. Even if presented with the same evidence, because PTAB’s proof of invalidity is the “preponderance of the evidence standard” rather than the district courts’ “clear and convincing evidence” standard, they may reach different conclusions.

In Delaware District Court, plaintiff Novartis’ patents, U.S. Pat. Nos. 6316023 and 6335031, were found to be nonobvious, but defendant Noven did not appeal this loss to the Federal Circuit. Novartis AG v. Noven Pharm. Inc., 2017 WL 1229742 at *2 (Fed. Cir. April 4, 2017).

While in a parallel proceeding, defendant Noven filed for inter partes review (IPR) where the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (“PTAB”) found the asserted claims as obvious and Novartis appealed to the Federal Circuit and argued that the PTAB “unlawfully reached different conclusions than … the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware, which addressed the ‘same’ argument and the ‘same’ evidence and found the Asserted Claims nonobvious.”

More specifically, Novartis’ argued that the PTAB improperly ignored the Delaware court’s conclusion that there was no motivation to combine prior art references Enz and Sasaki at the time of the invention.

The Federal Circuit started by noting that the PTAB requires proof of invalidity using the “preponderance of the evidence” standard, rather than by clear and convincing evidence as required in the district court litigation “meaning that the PTAB properly may reach a different conclusion based on the same evidence.” The Fed. Cir. quoted from Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 136 S. Ct. 2131 (2016), that a “district court may find a patent claim to be valid, and the USPTO may later cancel that claim in its own review…the possibility of inconsistent results is inherent to Congress’[s] regulatory design.”

Likewise, in Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. v. Roxane Labs., Inc., the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware held that the claims of Acorda’s patents were invalid as being obvious despite facing a higher burden of proof than at the PTAB, which previously held that the claims were valid. 2017 WL 1199767 at *40 (D. Del. Mar. 31, 2017) The district court recognized the PTAB’s opposing conclusion, but indicated that “two of the three references the PTAB considered are not part of the trial record here.” Id. at *41, n. 1.

Therefore, based on Novartis and Acorda, litigants should not expect the PTAB and the district courts to be bound by each other’s validity determinations.

Sixth Circuit Holds Proceding Martk with Term “Location” Reduces It to Merely Descriptive

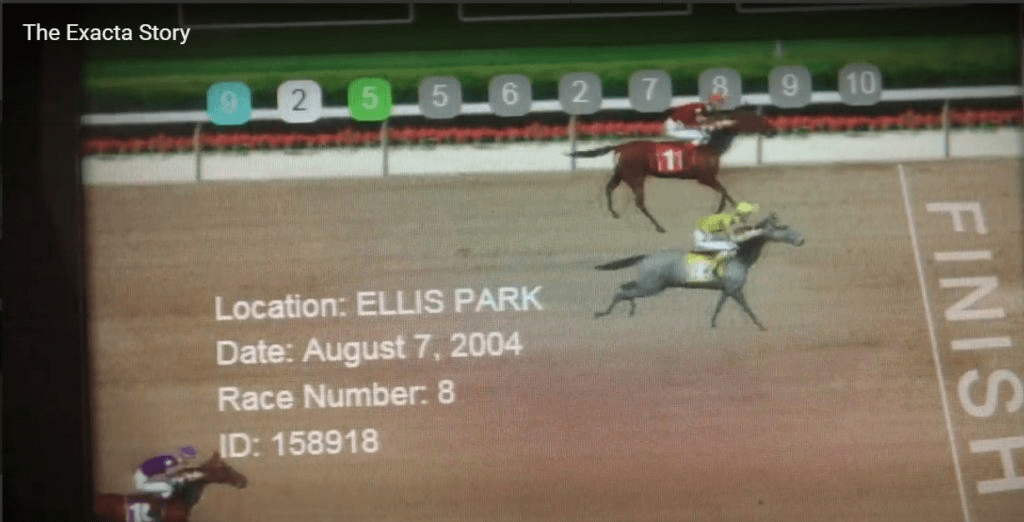

Takeaway: Displaying a trademarked location of historical horse race track locations in a simulation-based video game is considered non-trademark use.

Takeaway: Displaying a trademarked location of historical horse race track locations in a simulation-based video game is considered non-trademark use.

In Oaklawn Jockety Club, Inc. v. Kentucky Downs, LLC, (Sixth Circuit April 19, 2017), the Sixth Circuit affirmed a district court’s dismissal of a trademark infringement claim for use of plaintiff’s trademark in a videogame as it was not likely to cause confusion as to source.

The defendant’s use of the actual historic horse race track locations, such as Ellis Park, was found to be non-trademark use because they were used in a wholly descriptive way to identify the location of historical races.

The Sixth Circuit quotes the Supreme Court in Prestonettes, Inc. v. Coty, 264 U.S. 359, 368 (1924), “When the mark is used in a way that does not deceive the public we see no such sanctity in the word as to prevent its being used to tell the truth.”

The plaintiffs asserted that because the video games showed the names of their tracks on the video screen, consumers would incorrectly assume that the venues were the source of the recreations of the races displayed by video game.

However, the Sixth Circuit disagreed and stated that the “depictions are sufficiently different from the track owners’ product — live horse racing at their venues — that the minimal use of the trademarks, preceded by the word ‘location,’ would not confuse consumers into believing the videos were provided by plaintiffs.”

Register of Copyrights To Be Presidentially Appointed Position Passed by House

On April 26, 2017, the House of Representatives passed “Register of Copyrights Selection and Accountability Act of 2017’’ (H.R. 1695) by a vote of 378 to 48, to be confirmed by Senate, which amends Section 701 of the Copyright Act that the Register of Copyrights will be a presidentially appointed position for a term of 10 years. The Bill also created a panel, composed of the Speaker of the House, the President pro tempore of the Senate, the majority and minority leaders of both the House and Senate, and the Librarian of Congress, to recommend a list of at least three individuals for the President to choose from.

The Value of Patent Marking

Takeaway: Because damages for patent infringement without a patent marking is unavailable until the infringer has been given actual notice of the infringement, it is imperative to properly mark all patented products, and if not possible the packaging associated with the product.

Marking a patented product with the patent number provides “constructive” notice such that there is no need for any evidence for actual notice to mark the moment that infringement begins for the purposes of calculating damages.

Recently, in a suit against Samsung, Rembrandt Wireless Technologies was denied certain damages because one of the claims at issue was a claim in a patent that was not properly marked on sold patented products. Rembrandt Wireless Tech. v. Samsung Electronics, No. 16-1729 (Fed. Cir. 2017). Interestingly, Rembrandt attempted to delete the claim from the suit in order to recover damages from the time of the constructive notice of the other properly marked patented goods. This issue has been remanded to the district court for further consideration.

Patent marking is described in 35 U.S.C. § 287(a): “Patentees … may give notice to the public that [an article] is patented.” The preferred form of patent marking is placing the marking on the product itself, if possible, or alternatively, on the packaging used with the product, if marking the actual product is not feasible.

Further, if the patent application is currently pending, the only phrase that may be used is “patent pending” or “patent applied for,” however, they have no effect on future damage awards. In addition, be wary when marking products because false patent marking can be subject to a fine of $500 per incident.